YFN Stories: Ivie Uzebu

Ivie Uzebu is a writer specialising in the intersection between visual media and cultural criticism, driven by curiosity and fuelled by all things cinema, literary, and pop culture. Ivie was the successful applicant for an opportunity we offered to young people based in the South East to attend the Independent Cinema Office’s Young Audiences Screening Days 2025 in Manchester and write a blog post for us reflecting on what they learned from the sessions. With a particular interest in fresh, personal perspectives on how films are curated for young audiences, we were delighted to see Ivie’s insights into the course.

We Borrow the Cinema from our Young: A recap of the ICO’s Young Audiences Screening Days 2025

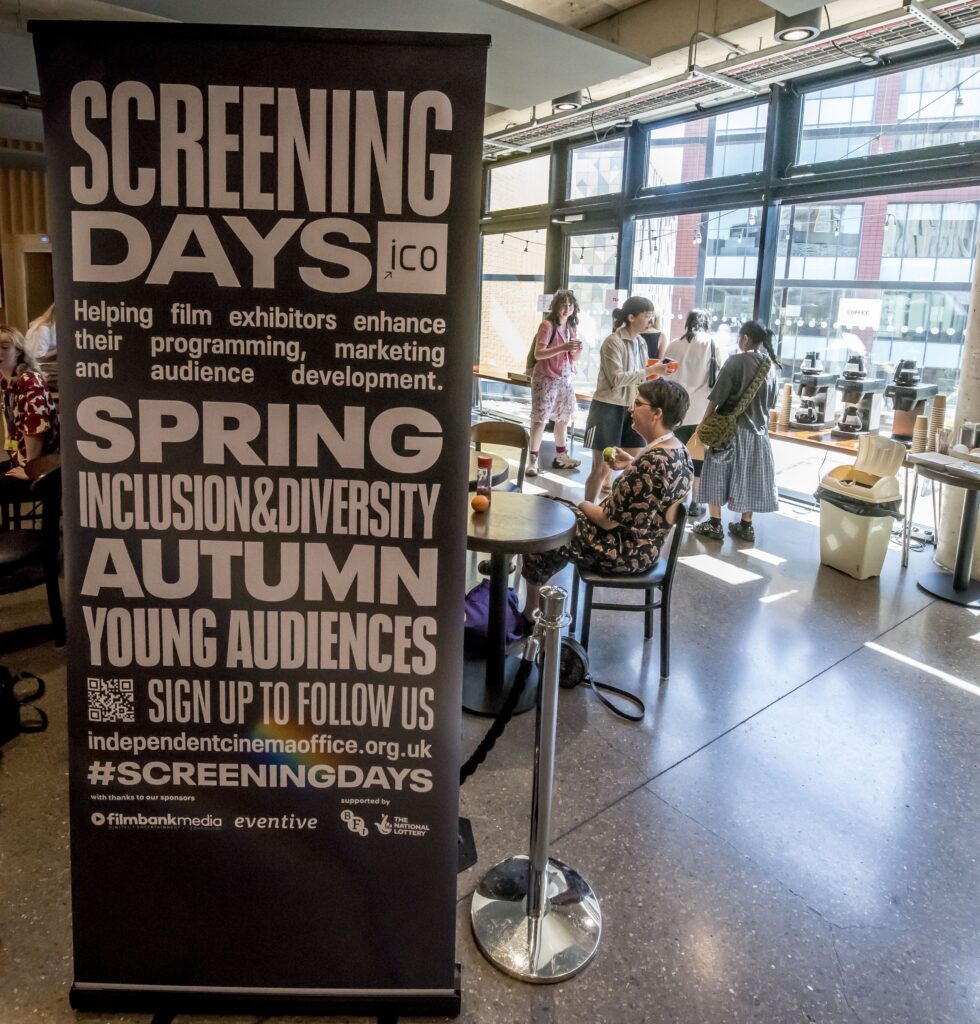

As a schoolgirl, cinemas were where I sought salvation, where I went to sit with others – no prying words or need for explanations, only the universal experience of ‘being at the movies’. When you are young, it feels as if there are not enough words to encompass the totality of your current condition – sometimes cinema feels truer than reality itself. With the highest overall level of cinemagoing being seen among younger adults, theatrical spaces as a sanctuary amidst our young people’s growing grievance with the disappearance of third spaces became an overwhelming sentiment of Young Audiences Screening Days 2025.

A recurring sentiment expressed in both the sessions and the film programme was the refusal to underestimate our younger audiences, to see them not only as children and young adults, but as people. “We want this audience to stay with us, to support and engage them from cradle to grave”, Alicia McGivern of the Irish Film Institute (IFI) reaffirmed.

Sometimes this means letting go of cinema etiquette altogether. This is for the children, so let’s make it clear from the moment they walk in the door that this is a space for them. The film practitioners reminisced as they recollected past events –– relaxed screenings with crafty, sensory-rich activities, children making shadow puppets on the projected screen, and providing a live score with maracas. It is not enough to provide a seat at a table; we must get rid of the table altogether, sitting on the carpet like morning circle time in primary school. By reconsidering the rigidity of theatrical spaces, we can dismantle this metaphorical table of wielded power and facilitate the expansion of younger audience engagement through amusement. But how do we create places of play and exploration, a community within spaces, and transform strange and peculiar venues into works of wonders?

Social Cinema’s programmer, Anna Peres, aptly shared the sentiment that it is the hostility of an environment which creates disability. By reimagining spaces, we lower the barrier of inclusion, transforming an empty corner into a quiet zone, a spare table into a changing area for older children, an old brewery into a viewing space (à la filmmaker Harry Lawson). Lawson placed materials at Newcastle Contemporary Art at children’s eye level, having a crouching audience instead of a tiptoeing one and, in response to the children’s reservations surrounding the austere reputation of galleries, encouraged visitors to run free. Created from the merger of The Cornerhouse and the Library Theatre Company, the hosting venue – HOME Cinema – is a fitting exemplar of reinvention. Beyond its impressive facilities, it proves itself a place of respite through a detail that would be easy to overlook: the venue’s washrooms are equipped with complimentary sanitary products.

With the rise of period poverty, sometimes the price of admission can be as miniscule as toiletries. It is imperative, now more than ever, that the theatrical space is a refuge, not merely a vessel for cinema, but a church for it, that it remains sacred amidst the threat of the passive moviegoing experience. According to 42nd Street Charity Senior Mental Health Practitioner Angeli Sweeney, sometimes it is enough to sit there and be an anchor for the younger members of our community, regardless of whether they engage or not, and to respect that. By creating social spaces that exist long before the previews and well after the credits roll, we yield a transitional space where they can linger, all the same.

A resounding sentiment shared by the curators was a call for perseverance and to welcome the unpredictability of programming for younger audiences. (Alicia McGivern recalled a guest speaker dropping F-bombs and teaching a predominantly vegetarian audience how to snare a rabbit, much to the team’s dismay but the children’s delight!) With almost a third of UK independent cinemas believed to be at risk, delivering events despite restrictions is a triumph in itself. In the eyes of CULTPLEX’s Greg Walker, failure is a baptism of sorts. Despite dialogue surrounding budgeting and financial constraints, the question of “how do we protect our cinemas?” remained unresolved. Although the practitioners differ in their approach, the passion they give and receive from audiences is unanimous. Borrowing Marie Kondo’s central question, Barbican film curator Suzie Evans asks, “does it spark joy?”. Evans reminds us that the role of a programmer is to ultimately “look under cinematic rocks as film detectives”, to see how long the rope is and keep pulling at the thread as we find new ways to present international and arthouse cinema to young audiences in the everlasting haven of the cinema.

ICO event photo credit: Chris Payne